New Delhi, India — In 2014, Narendra Modi swept to power in India with his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) pitching him as an economic reformer who would root out corruption and rescue the aspirations of India’s middle class from the clutches of elites – as well as the hellscape of rising prices and unemployment.

Ten years later, as Modi contests for a rare third term, the gap between rich and poor in India – already significant in 2014 – has widened into a canyon, economic researchers warn. India’s income and wealth inequality have become among the highest in the world, worse than in Brazil, South Africa and the United States, reveals a new study by the World Inequality Lab (WIL).

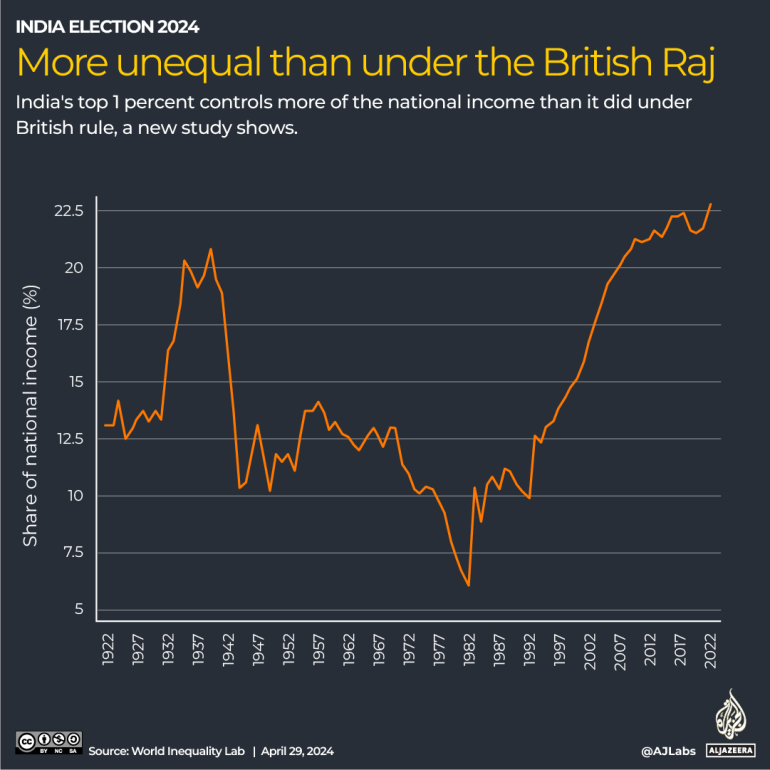

As India votes in national elections to choose its next government, the research in the recently published The Rise of the Billionaire Raj shows that income inequality in the country is, in fact, worse than it was under British colonial rule. The study was co-authored by Nitin Kumar Bharti from New York University’s Abu Dhabi campus; Lucas Chancel from Harvard Kennedy School; and Thomas Piketty as well as Anmol Somanchi of the Paris School of Economics.

The widening wealth gap in India has emerged as a political flashpoint, with the opposition Congress Party promising that if elected, it will carry out a caste census that it claims will show how traditionally disadvantaged communities have suffered under Modi’s rule.

But just how unequal is India, according to the new research? What are the reasons? And what are the potential solutions?

Through much of the 1930s, when the British ruled India – which was known as the crown in the jewel of the empire – the richest 1 percent held just more than 20 percent of the national income. That share dropped during World War II, reaching to just above 10 percent through most of the 1940s, and about 12.5 percent in 1947 when India gained independence.

It hovered there until the late 1960s. Then, as India implemented a series of broadly socialist moves under then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi – payments made to formal princely kingdoms, as compensation to get them to accede were scrapped, and banks were nationalised, among other steps – the national income share of the top 1 percent collapsed to about 6 percent by 1982.

As India liberalised its economy in 1991, things started to change. By the turn of the century, the 1 percent held more than 15 percent of India’s income. By the time Modi came to power in 2014, that figure had crossed 20 percent.

And by 2022-2023, it touched an unprecedented 22.6 percent.

India’s fast-growing economy – its gross domestic product (GDP) is growing by more than 7 percent annually – only appears to be accelerating that gulf, researchers say.

“When the economy grows faster, then a pie growing bigger quickly also leads to increasing inequality,” Bharti, the lead author of the WIL study, told Al Jazeera. “We thought that the free market would take care of it but it has not.”

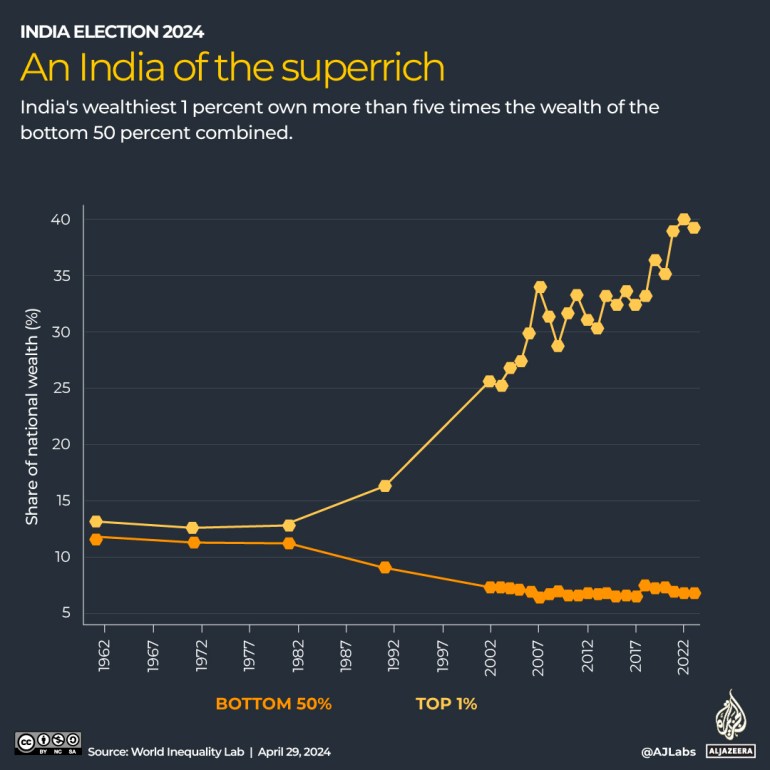

If India’s income inequality is vast, its wealth imbalance is starker. The top 1 percent controlled less than 15 percent of the national wealth in 1961, when the researchers began their analysis. Today, their share is at more than 40 percent.

The richest saw their relative wealth stay mostly static during the pre-liberalisation period, before it took off in 1991, crossing 20 percent before the turn of the century. It stood between 30 and 35 percent when Modi took office – and when the prime minister convinced India that he would deliver them from their economic struggles.

Yet, a decade later, as Modi campaigns for re-election, the mounting inequality suggests that many Indians are struggling as much, if not more, than they were in 2014. Whether that will affect the ongoing election though is unclear, said development economist Jayati Ghosh, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“It is the same electorate that was addressing the major economic issues until 2014, like corruption, economic stagnation, unemployment, poor livelihood, inadequate public services,” said Ghosh.

But Modi’s campaign, in recent days, has shifted towards religious polarization and strayed far from the economic promises of 2014. For instance, Modi accused the opposition Congress Party of plotting to give Indian Muslims first rights over national resources, and apparently referred to Muslims as “infiltrators”.

“The current regime is obsessed with narratives,” said Ghosh. “The common man is far away from the dark reality.”

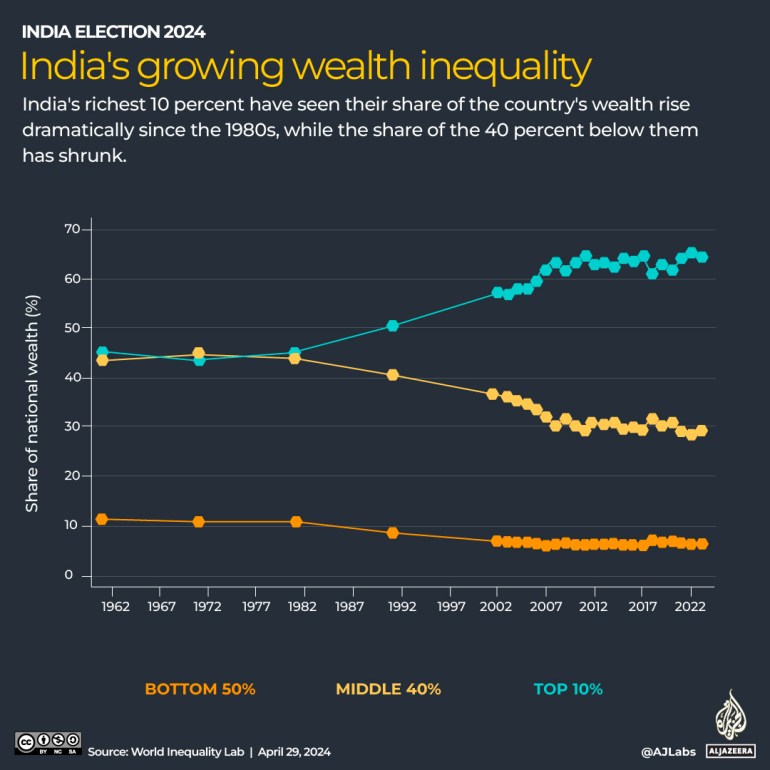

If the top 1 percent hold more than one-fifth of the national income, the top 10 percent control almost 60 percent, the study reveals. In the years after independence, that figure for the top 10 percent had fallen to 30 percent in 1982, before picking up, especially after the 1991 liberalisation measures.

The top 10 percent also hold about 65 percent of the nation’s wealth.

The accumulation of income and wealth in a few hands has come at the cost of the remaining 90 percent. But the data show that it is the middle 40 percent of Indians whose share of national income has shrunk the most, faster than even the bottom 50 percent of the country’s adult population, said Bharti.

The national income share of the middle 40 percent of Indians fell from above 45 percent in the early 1980s to about 27 percent in 2022. For India’s poorest half of the population, the share of national income fell from above 23 percent to 15 percent in this period.

That prospects of relative upward mobility have slowed – not improved – for the Indian middle class is not surprising, experts say.

Rishabh Kumar, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston, whose research focuses on historical inequality, underlined that the privatisation of the Indian economy, coupled with globalisation, favoured those with a higher level of education, which allowed them to compete internationally. And in India, that kind of education access has traditionally been skewed towards the wealthy and upper-caste communities.

“The only opportunity for transformation for anyone in the middle class is to play a lottery and get into one of these very few institutions that can propel you to a white-collar job,” Kumar said.

That lottery is paying off for only a few. Consider this: The richest 10,000 Indians have an average income of 480 million rupees ($5.7m) a year – more than 2,000 times the average income of Indians.

The national average income itself, of about 200,000 rupees ($2,400) per year, is misleading, because, as Kumar points out, the new research shows that only individuals on the cusp of entering into the top 10 percent earn that much. “So 90 percent of the population is not even making the GDP per capita of India [the same as the national average income],” Kumar said.

“This paper is a reality check for a lot of Indians about the distribution of goods in the present society,” said Kumar. “And clearly, the rich are benefitted more than the others in India.”

Just how good are things for the very wealthiest of Indians? The rest of the country got a three-day-long peek as many of the world’s top-1-percenters gathered in early March for the pre-wedding celebrations of Anant Ambani, the son of Asia’s richest man Mukesh Ambani, which cost a whopping $120m. The national media gave a detailed breakdown of the meals on offer, dish by dish, which a Guardian writer noted, “even Nero might have thought a little over the top”.

With a private Rihanna concert, where attendees included Bollywood A-listers, Mark Zuckerberg and Ivanka Trump among others, the extravaganza was an exhibition of the dramatically widening income gulf in India.

When India’s economy liberalised in 1991, it had one dollar billionaire. That rose to 52 in 2011, then 162 in 2022, according to the new study. Since then, that number has exploded further to 271 – third behind only China and the US – according to the Hurun Global Rich List for 2024.

Between 2014 and 2022, the net wealth of Indian billionaires grew by more than 280 percent – 10 times faster than the growth in national income over this period, by 27.8 percent, as per the annual Forbes lists of the richest individuals in the world.

On the other hand, India is home to a quarter of all undernourished people worldwide and scored 28.7 out of 100 on the 2023 Global Health Index Severity of Hunger Scale. Between 2019 and 2021, approximately 307 million Indians experienced severe food insecurity (not having enough to eat), while 224 million people were affected by chronic hunger.

The WIL report captures other indicators of India’s sharpening inequality, too: It cites other research that shows how just 1 percent of Indians take 45 percent of all flights in the country; only 2.6 percent of Indians invest in mutual funds; and 6.5 percent of Indians are responsible for 45 percent of all digital payments.

The divide extends to the dining table: 5 percent of users account for a third of all orders on Zomato, India’s largest food delivery app.

The concentration of wealth at the top is a pattern also visible within the top 10 percent, Bharti said. “We see largely similar trends for the top 0.1 percent, top 0.01 percent, and top 0.001 percent,” he said.

Looking back at the BJP’s 2014 poll promises, Bharti said that “what we are actually observing 10 years later in terms of inequality is exactly the opposite of the pitch, with the middle 40 percent losing and the top 1 percent gaining”.

“[The BJP government] has created a small set of the population who are super wealthy where a lot of wealth accumulation is happening,” he added.

Kumar, the associate professor of economics, agreed: “Most of the buyer growth is going to somebody else and much of this growth is very concentrated.” As a result, he said, “we can just see the rich getting richer at a faster pace than everyone else”.

This is leading to a scenario where even the modest dreams many poorer Indians once harboured appear to be in crisis.

“Things that used to be the aspirational purchases of the relatively poor, like a two-wheeler, have stagnated,” said Ghosh, the economist, referring to periods in recent years when sales of scooters and motorcycles have struggled – even as sales of luxury goods, by contrast, appear to have done relatively well.

“That clearly shows the inequality of income and wealth. You are selling Mercedes but not motorcycles.”

At least some of the factors driving this deepening income gulf are structural and linked to India’s broader journey since it liberalised its economy in 1991, experts say.

India has struggled to pull the 45 percent of its workforce involved in agriculture towards more productive and better-paying employment, in part because its education system has focused less on them and more on the “tertiary education of elites”, said Bharti.

In essence, Ghosh said, India’s economic boom over the past quarter of a century has been “based on inequality because it just benefitted the top 10 percent while the formal economy has sustained on unpaid and underpaid labour”.

But global events and Indian policies in recent years have also compounded these challenges.

“Unfortunately, three big policy shocks – demonetisation, introduction of GST (Goods and Service Tax) and the COVID-19 lockdown – really hit the informal sector disproportionately,” Ghosh said. “[The Modi government] attacked the livelihood and employment of the dominant part of the workforce with no remedies.”

Demonetisation refers to the overnight announcement by Modi, in 2016, that all high-value current notes would be discontinued. This led to a crisis that hit the small savings of millions of Indians and the liquidity of vast swaths of India’s small-scale industries.

The Modi government introduced a GST in July 2017. And in the spring of 2020, as COVID-19 started spreading, the government imposed a nationwide lockdown that it said was needed to limit the reach of the pandemic – but that cost tens of millions of migrant workers their jobs and crippled small-scale businesses.

The WIL study also observed that the Indian income tax system might be regressive when viewed from the point of view of net wealth – that is, the more wealth taxpayers own, the less taxes they pay as a share of their assets.

The authors of the WIL study have called for the implementation of a “super tax” of 2 percent on dollar billionaires and multimillionaires as “a tool to fight inequality”, in addition to restructuring the tax schedule to include both income and wealth.

According to Bharti, the solution to inequality lies in education. “India needs to create the right set of human capital depending upon the jobs you want to create and align them,” he said. “[The government] needs to adapt the education system vis-a-vis market or India will keep producing unemployable graduates.”

Meanwhile, the Communist Party of India (CPI) – a small but not insignificant presence in the country’s political landscape – proposed a “wealth tax and inheritance tax” to keep the nature of the economy “more equal, just, and egalitarian” in its 2024 election manifesto.

“Unemployment and price rise have become the biggest woes for the people. BJP’s rule has resulted in unprecedented concentration of wealth at the top while the poor are pushed to destitution,” said the party’s general secretary, D Raja.

The manifesto of the Congress Party, the country’s main opposition, said it was “opposed to monopolies and oligopolies and crony capitalism”, promised to “re-set the economic policy”, and tackle the BJP’s legacy of “job-loss growth”. Yet, after Modi attacked the Congress, suggesting that it wanted to take wealth from families and give it to Muslims, the opposition party has said it has no wealth redistribution plans.

Asim Ali, a political commentator, said a “relative absence of popular movements led by the opposition” allows Modi and the BJP to largely evade questions on inequality by focusing on Hindu majoritarian politics. That is why, “these adverse economic conditions will not necessarily hamper [the BJP] in the coming election”, he said.

To Ghosh, the rising inequality is unsustainable for the Indian economy and society. “I do not think this inequality can continue indefinitely but when it will change – who knows?”