In November 2024, two important global reports on Indian farming support estimates were released, presenting starkly contrasting views on India. On 7 November, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development published its producer support estimates, highlighting the extent to which Indian government policies taxed farmers. Just four days later, the United States delegation at the World Trade Organization released calculations asserting that the Indian government’s support to its farmers was excessive and high.

These contrasting perspectives from two prominent global platforms raise a crucial question: What is the reality of farming support in India? We delve into this irony below.

PSE assesses farmer support under two sub-components:

Budgetary support: Every budgetary support that the Government of India (GOI) directs to farmers is counted under this head. It includes direct subsidies, payments based on production, input subsidies, and other financial incentives. This also includes payments under Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN). The higher the budgetary support, the greater the PSE.

Market price support (MPS): This component measures the price support, if any, that a government provides its farmers. This measure is crop-specific, and crops covering 80 per cent of India’s agricultural value of output are studied for PSE. MPS is the difference between the domestic price of a crop/commodity and its international market price, multiplied by the quantity produced. It is assumed that after adjusting for the crop’s quality and global freight, domestic and global prices should be similar. Any sustained difference in prices should be reflective of structural issues and/or policy-induced distortions. The value of support under a crop is estimated by multiplying its MPS with its crop size. The higher the MPS, the higher the PSE.

If there is an export ban in India and global prices of the crop are higher, then MPS for that crop will be negative. This implies that in case the government had not imposed the ban, the domestic prices would have been higher than their current levels. This implies the farmers of that crop are taxed as prices are being maintained lower than what they would have been in the absence of export restrictions.

The PSE helps evaluate the level of government intervention in agriculture. By following the same methodology across countries, the OECD estimates enable comparisons across countries and time periods, highlighting which agricultural policies are most supportive or distortionary. High PSE values suggest a strong dependence on government support. These estimates are crucial as they can influence international trade negotiations and discussions about sustainable agricultural practices.

Also read: India’s edible oil market is facing reduced demand. Increased import duty not a fix

The OECD PSE measures the economic impact of government policies on agriculture. It provides a real-time reflection of how current policies affect farmer prices and sales.

In contrast, the WTO’s Aggregate Measurement of Support (AMS) assesses compliance with trade commitments under the Uruguay Round. Unlike the OECD PSE, it does not completely reflect current market conditions, prices, or currency values. Instead, it uses a fixed “administered price” (such as India’s Minimum Support Price or MSP) and a constant reference price based on the 1986-88 average.

For example, in the released WTO report, the price gap for wheat was calculated as the difference between the administered price (Rs 19.75/kg MSP for 2021/22) and the historical reference price from 1986-88 (Rs 3.54/kg). The resulting gap (Rs. 16.21/kg) was multiplied by total wheat production to estimate support. Among other things, this method has two major issues: (i) it compares current prices to historical prices without adjusting for inflation; and (ii) it assumes that MSP benefits apply to the entire crop, not just the quantity procured. As per NSO’s Situation Assessment Survey (SAS) 2018-19, only about 9 per cent of Indian farmers reported to have benefitted under MSP. If all rice and wheat produced in the country genuinely benefited from MSP operations, as assumed by the WTO’s methodology, mandi prices in states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and parts of Uttar Pradesh would not consistently fall below MSP.

Overall, while the OECD PSE is dynamic and reflects recent policies, the WTO AMS uses static benchmarks and assumptions for legal assessment.

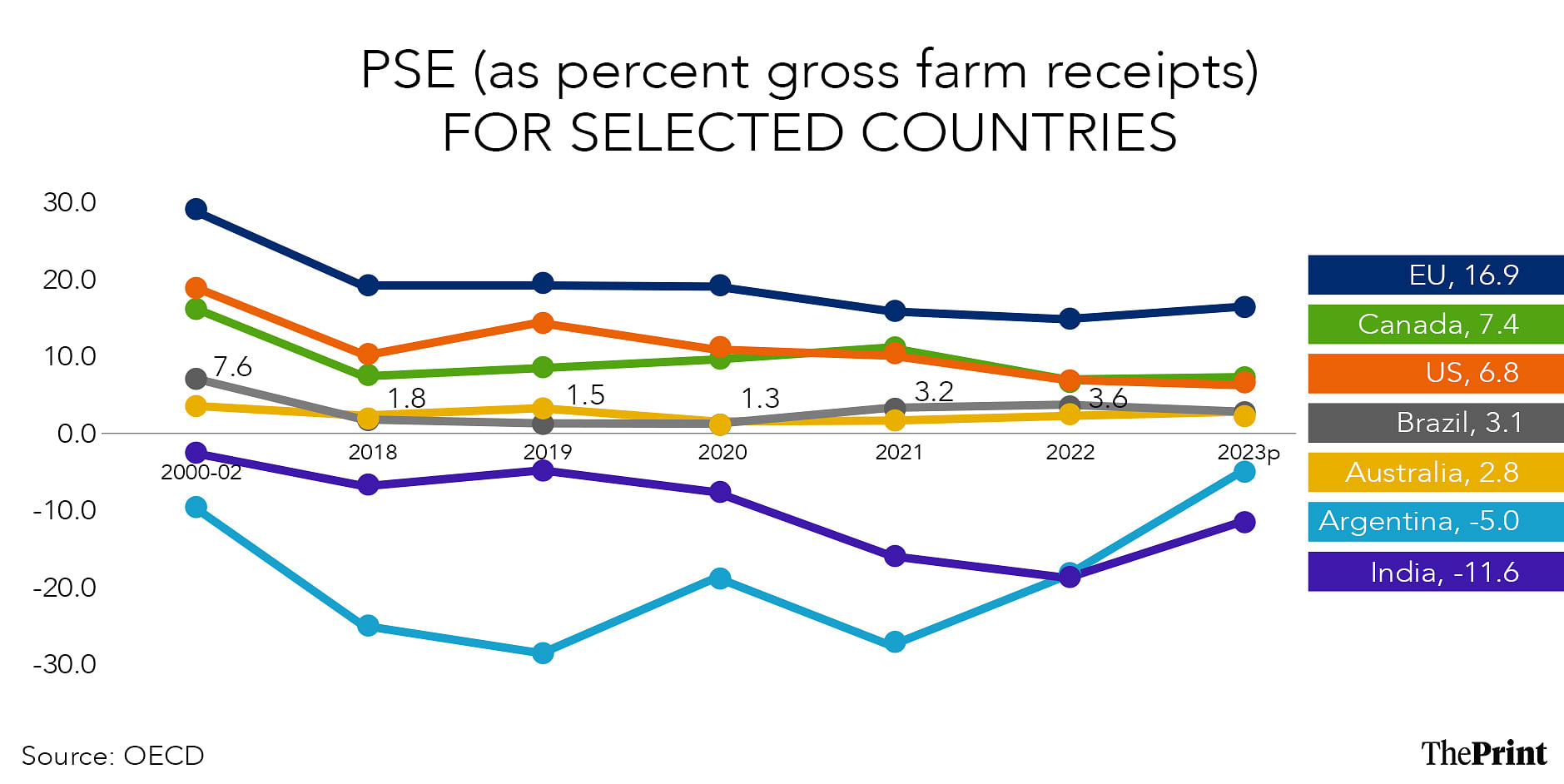

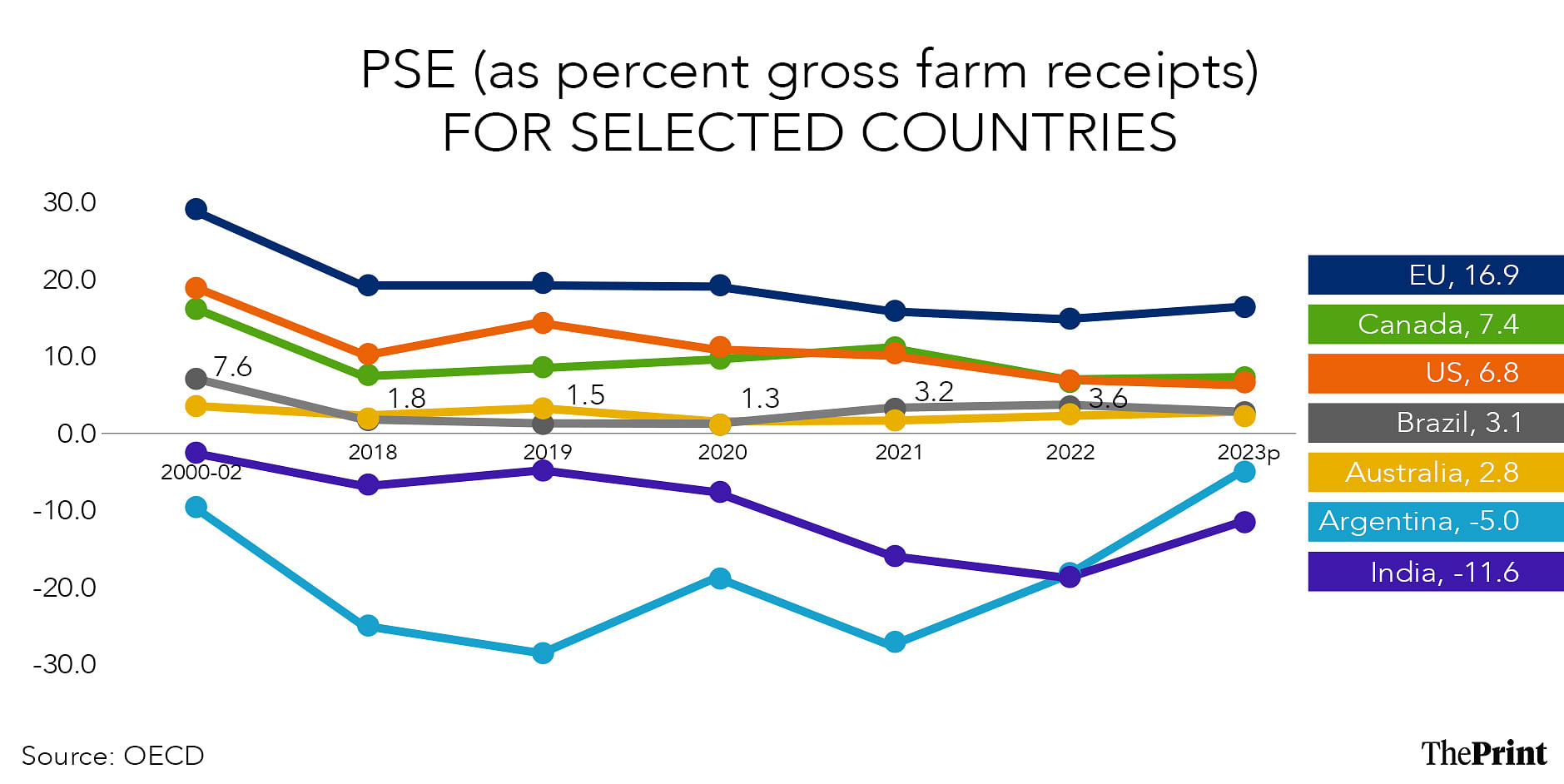

Indian PSE for 2024 is estimated to be about -11.6 per cent. This implies that the Indian farming community lost about 11.6 per cent of its revenues (including from the sale of produce, support payments from the government, and subsidies like fertiliser and electricity), due to government programmes and policies in the year. This number for the European Union (EU), for example, was 16.9 per cent, implying that about 16.9 per cent of the revenue earned by EU farmers was on account of government support programmes.

According to the average PSE estimates for three years (2021, 2022 and 2023), farmers in Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, and Korea received the highest support from their respective governments (PSE exceeded 40 per cent). Japan’s was 33 per cent. The United Kingdom, the EU, and China offered support levels below 20 per cent but still above the 54-country average of 9 per cent. Indonesia, Colombia, the US, and Canada maintained support levels ranging from 5 per cent to 9 per cent. Like India, farmers in Vietnam and Argentina suffered from negative support.

The irony currently surrounding India’s agricultural support is twofold:

Disparity in global standards: Countries like the US, Brazil, Canada, Australia, and Norway provide extensive subsidies to their farmers, yet these are not deemed violations of WTO rules. For instance, US subsidies to cotton farmers exceeded 75 per cent of the production value in several years, with over $40 billion provided between 1995 and 2020. In contrast, India’s support is labelled excessive, largely due to WTO’s reliance on outdated benchmarks. Comparing current prices to those from 1986-88—a period of significantly lower global prices—inevitably skews the analysis, portraying India’s support as disproportionately high. Real-time and current price benchmarks are essential for fair assessment.

Conflicting global narratives: The second irony lies in the contradictory assessments by global platforms. While the OECD views India’s policies as implicitly taxing farmers, the WTO calculations claim excessive support. This divergence raises questions about how the same set of policies can yield such opposing conclusions about their reach on farmers.

These inconsistencies highlight the complexities of WTO negotiations for India, suggesting that the challenges extend beyond the apparent discussions on the table. Addressing such disparities requires a nuanced approach to global agricultural policies and support mechanisms.

The WTO’s influence and its trade commitments are globally significant, especially for countries like India. These are binding legal obligations that nations must adhere to. However, discrepancies in methodologies—such as the WTO’s AMS calculation—raise concerns affecting millions of Indian farmers. If the AMS system assumes nationwide MSP benefits while ground realities show otherwise, this methodological issue needs urgent attention.

It is untenable that one global report highlights Indian farmers as under-supported or even taxed, while another accuses the Indian government of providing excessive support. This contradiction underscores the need for reforms in how agricultural support is assessed globally, ensuring methodologies reflect actual farmer realities rather than theoretical assumptions. Addressing these discrepancies is essential to maintain fairness and transparency in international trade negotiations.

Saini is an agriculture economist and CEO, Arcus Policy Research. Hussain is former Agriculture Secretary, GOI and CMD, FCI.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)